|

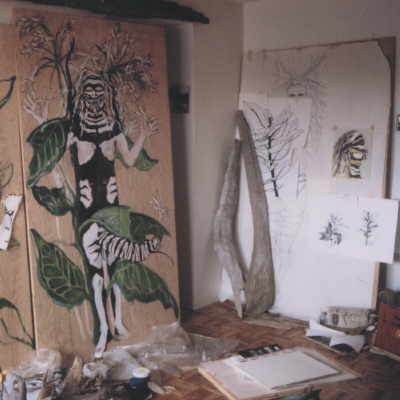

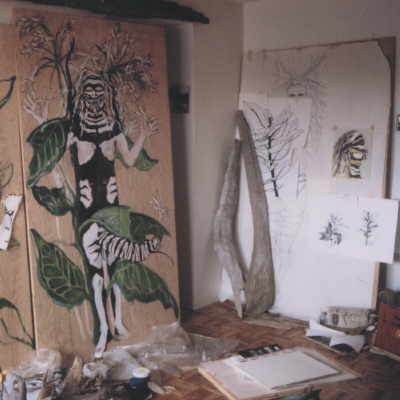

Questions about the

installation Milkweed Patch

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Where did you get the

idea?

|

|

|

I always loved science, but we were told that one had to

choose between the arts and the sciences. I chose art

because I knew my imagination would always be a distraction,

perhaps to the point of insanity, if I couldn't somehow

harness it.

Milkweed Patch began with watching

caterpillars. When I was a kid, Toronto entomologist Fred

Urquhart had sent out a call for volunteers to tag monarchs,

to find out where they migrate to in the fall. A lot of the

people who ended up being important to that research were

children, but I wasn't one of them. There are no monarchs in

Alberta, so I practised putting sticky labels on a few

unfortunate common sulphur butterflies. I was ecstatic to

see them when I moved to Ontario, but by then I was a busy

adult person, with no time to be proccupied with

butterflies.

|

|

|

But in 1989, during an emotional break-down, a friend let

me spend a lot of time at her home in the country. That year

the monarchs were abundant, and their chrysali festooned the

eaves like little jade lanterns. I had the time to watch the

monarchs closely. I began to identify with their lives. So

Milkweed Patch began with drawings and photos

made on Manitoulin Island in 1989 and 1990. It was shown as

a work in progress at Cedar Ridge Gallery in Scarborough,

Ontario and the Cornwall (Ontario) Regional Art Gallery. It

made its debut in its final form at A Space Gallery in 1999,

where the pictures were taken that are featured on this

web-site.

My educational work is also based on the process that

created Milkweed Patch. Through my educational

projects I try to let children know, not that they have to

rescue Nature from us, but that Nature is there for them, if

only in a crack in the sidewalk. She can help them through

hard times, teach and entertain them. They don't have to

have gobs of money to feel fully alive, to create.

|

|

|

|

|

If you like butterflies so much,

how can you use silk? To make the silk you used in your

artwork, millions of pupae were boiled alive inside their

cocoons!

|

|

I wanted to use silk for its beauty, and the fact that it

is a real insect product. Some artists, such as Canada's

Aganetha Dyck, collaborate with animals like beavers or bees

to make artwork. Milkweed Patch did not

involve a collaboration, but a large-scale sacrifice of

insect life. This was appropriate for an artwork that, among

other things, tries to confront our fear of death.

Milkweed Patch grew from grief caused

by a large-scale human loss during the AIDS epidemic: one

that swept through my friendships from about 1987 to 1993

and that is still growing in Africa and worldwide. Often my

personal mourning combined with fear for the fate of the

migrant monarch butterflies. Insects died, people died

during the making of this work. In a real way, the insect

tragedy represents other losses, including personal ones

experienced by viewers and environmental disasters such as

the large winter kills due to deforestation of the monarchs'

Mexican refuge.

Most of all, my purpose was to create the opportunity to

make an important point. Animals generally don't become

extinct because we use them, but because we destroy the

habitats in which they live. I respect vegetarians,

especially in view of the tremendous cruelty, waste and

habitat destruction that accompany our industrial farming

and fishing methods. But the use of animals for food and

clothing needn't involve any of this. Aboriginal traditions

teach us that respectful and sustainable use of the land,

not abstention, is basic to an ecologically sustainable

economy. They teach that we can take with respect,

gratitude, love and intelligence.

Herein lies the key to united action among

environmentalists, First Nations and resource workers such

as loggers, trappers, farmers and fishermen. Many of us have

a "Sunday" attitude toward the earth. We want a few pristine

areas set aside for our enjoyment, but we figure our farms

and cities are hopeless. This is not the case. The continued

existence of large areas of true wilderness is necessary for

the health of all the living systems we depend on: air,

weather, water, soil, the regeneration of our foodplants and

animals. But wilderness has always included a human

presence.

And if we want to improve our health now and permit today's

children to have a real life and a living, we must use the

land with respect always. All over the world, traditional

methods have been in use that filled the needs of dense

populations century after century. Over the last thirty

years, new technologies and working methods have been

developed for industry, farming, energy and civic design

that would create good jobs that solve problems and perform

vital services.

The way that resources are taken now results in layoffs of

millions of workers as a fishery or forest is destroyed, but

knowledge from the past and the present exists to replace

needlessly destructive ways of managing economies. The use

of silk in Milkweed Patch makes the subtle but

vital point that respect for life needn't force one to live

like a Jain monk. In any but the most short-sighted

scenarios, ecological sense also makes economic sense.

|

|

|

|

|

There seems to have been a

native influence on your art.

|

|

|

There definitely has been. But nobody had to tell me that

it is disrespectful to try to imitate someone else's

culture, or that insights must be earned and not borrowed. I

knew I would lose my friendships among native people if I

exploited our relationships in any way. So I'm concerned

about the issue of cultural appropriation.

I benefited greatly from knowing more than one culture, and

the chief benefit is to know that I wasn't crazy to feel

uncomfortable with aspects of my own. My culture isn't

reality: it's my culture. It's the legacy that I was given,

and that I can influence as I pass it on. That awareness

helps me to accept myself and to explore reality with

greater freedom, though often with some discomfort. I use

what I learn to try to develop and heal my own culture so

that it will stop being so destructive.

Most native teachings are freely shared, and two were of

special benefit to me. One was the belief, not metaphorical

at all, that plants and animals are our healers and

teachers. This confirmed the way I had always felt toward

other creatures, and was a needed source of strength.

Another very helpful teaching was that it's our duty to use

the gifts the creator sent us into the world with. In a

lifelong struggle with creative block caused by my own

culture's contempt for artists, that was the mantra that

enabled me to sit down and start moving my hands each time I

worked on a piece.

|

|

Originally, the drawings and paintings I created under

these insights bore too much resemblance to various types of

aboriginal art. (See Humanoid Skull, at right)

I abandoned that approach to try to make an original

statement. As I explored my own identity, I remembered the

ten-year-old who wanted to be a scientist. Returning to my

original observations of the monarch butterfly, I began to

base my drawings on biological illustration. It was

gratifying to realize that biology's first and best

technique, the observation of wild nature, is also the basis

of aboriginal teachings worldwide!

|

|

|

I finally was beginning to like what I was doing, but the

small scale of my drawings made them seem more precious than

transformative, like fairy tale and nature illustrations. In

order to help the viewer sense the power and terror of

metamorphosis, and to firm up the association with human

life cycle, I scaled the project up to human size. Without

my conscious effort, other cultural references seep in, from

Carl Jung to Odilon Redon to Lewis Carroll. The process was

long and and the results are kind of strange. But after

watching many people walk through the installation, I don't

doubt that Milkweed Patch is the complex yet

accessible, all-ages experience I wanted it to be.

I'm impatient with those who would dismiss this honest

struggle by labelling my concerns as "politically correct".

Respecting other peoples' boundaries forced me to dig deeply

into myself and my culture, always a rich creative process.

I feel that through this pursuit I managed to hit an

aquifer: the relationship to nature that sustains us all and

that we are all entitled to. It's so important for my

industrialized culture to find ways to make that connection

in all fields: science, ethics, social organization.

Aboriginal cultures tell us that a rich life is possible, in

harmony with the earth. But we can't save ourselves by

playing Indian. Other cultures can teach and guide us, but

my people must dig our own way out of the immense darkness

we've created.

This was a long answer to a short question, but its an

important question.

|

|

|

|

|